Not a Breakthrough, Just Direct Carbonation of Lithium

Every week, the media crowns yet another “revolutionary” breakthrough in lithium-ion battery recycling, processes that industry insiders and researchers have known about for years, hidden behind vague patents and proprietary walls. To the average reader, however, many variants of these processes are sold as game changers. Cue the latest one that popped up in my feed.

China’s ‘fizzy’ method recovers 95% lithium from dead batteries with just CO2, water

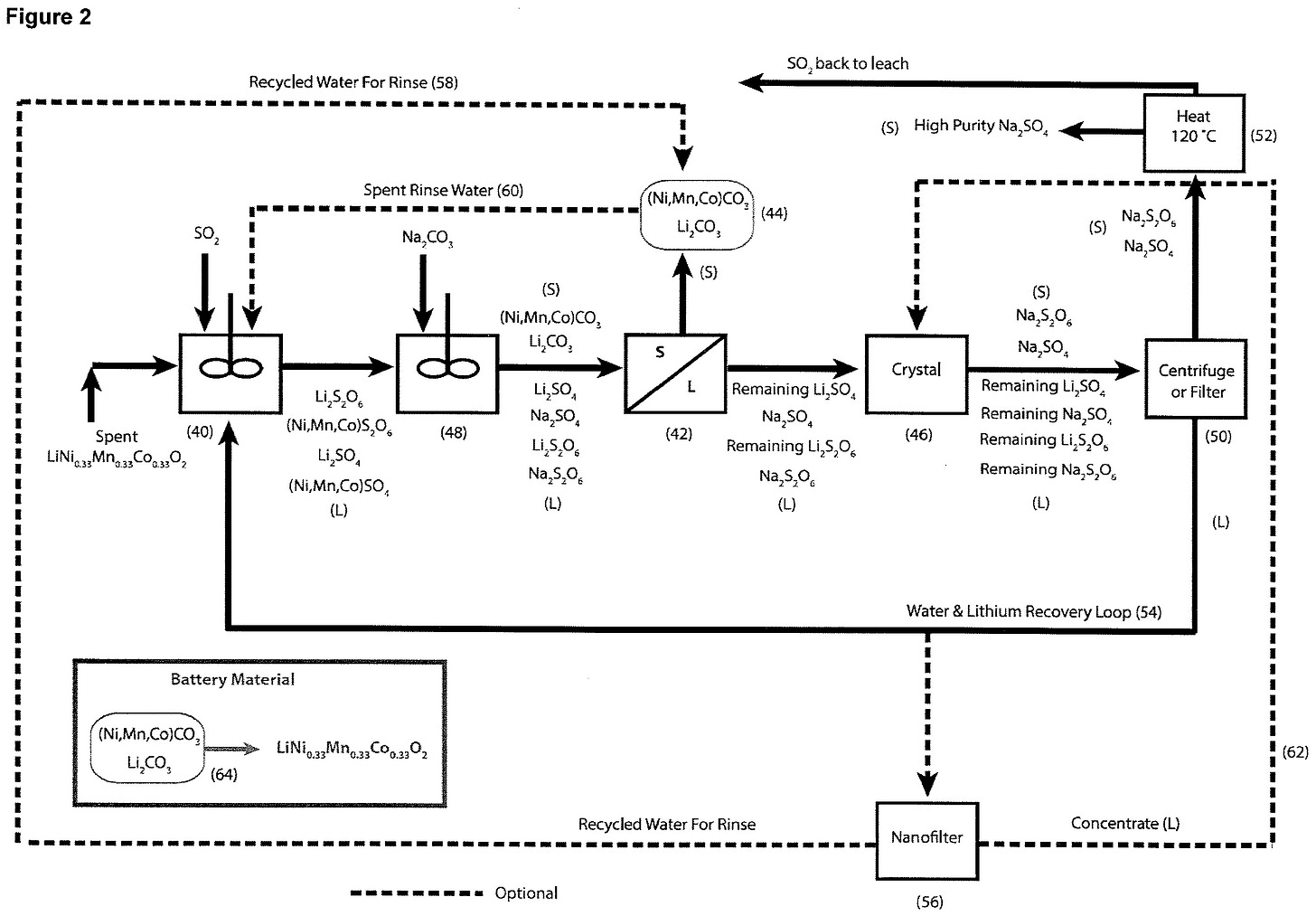

Direct carbonation is a process where lithium-bearing solutions react directly with carbon dioxide to form lithium carbonate. By introducing CO2, the process precipitates lithium carbonate directly from the black mass. In lithium-ion recycling, this is often called early-stage recovery. Lithium is extracted directly as a carbonate rather than as an intermediate such as lithium sulfate. This approach is not limited to recycling. It is also used in lithium refinement, including at LAC 0.00%↑ Thacker Pass, to convert conventionally produced lithium carbonate into battery-grade. This is a simplified flow sheet based upon their National Instrument 43-101 Technical Report for the Thacker Pass Project

Lithium carbonate is crystallized from lithium sulfate using soda ash.

The crystals are dewatered and washed.

The solids are converted to soluble lithium bicarbonate by reacting with CO2

The lithium bicarbonate solution is filtered to remove insolubles.

Lithium bicarbonate is recrystallized back to lithium carbonate.

CO2 is captured and recycled to the process.

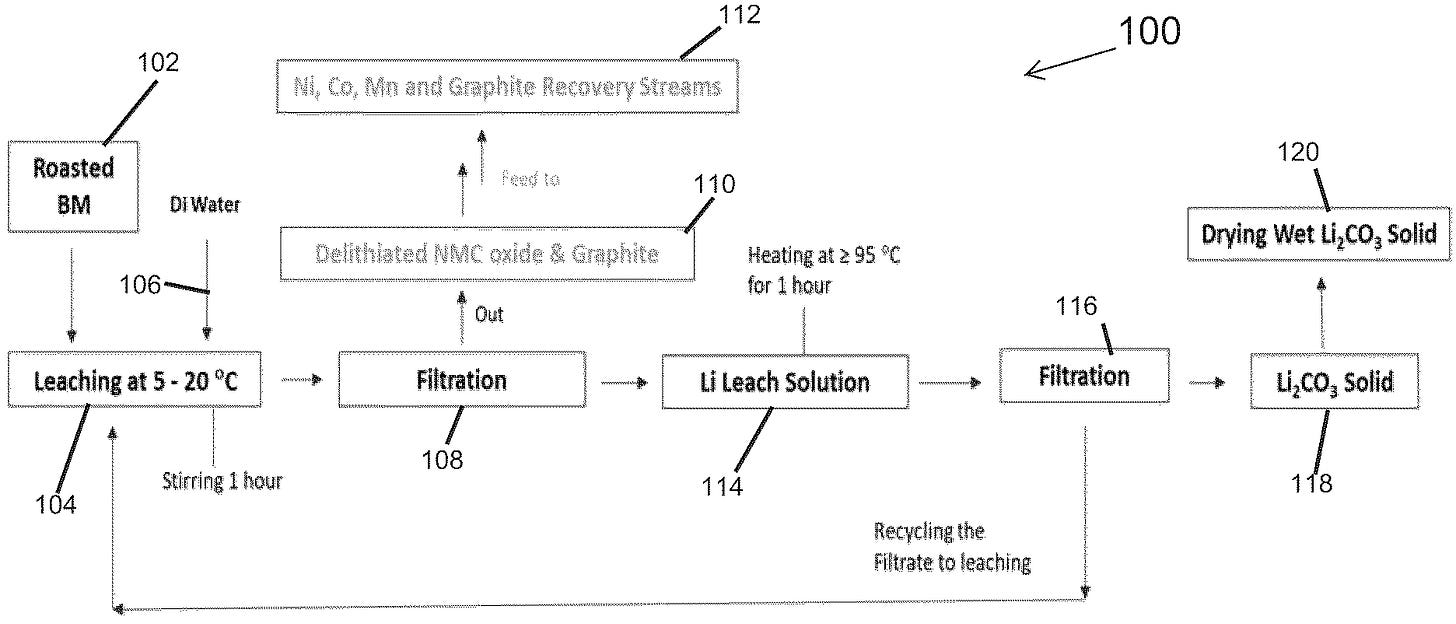

An example of a lithium-ion recycling company that uses direct carbonation is CyLib. CyLib is a German company and their process uses direct carbonation to convert lithium in black mass into a water-soluble form, which is then further processed to produce battery-grade lithium carbonate. This is a simplified flow based upon their patent.

Pyrolysis with CO2: Black mass is roasted at 300 °C–800 °C in a CO2 atmosphere, partially carbonating lithium while CO2 is also generated from cathode and binder decomposition.

First lithium extraction: Water is added to leach lithium as lithium carbonate. Additional CO2 may be introduced to form carbonic acid, improving lithium dissolution.

Flotation (optional): CO2 assists in separating graphite from the lithium solution.

Second-pass purification: Lithium carbonate is redissolved in water and CO2 to form soluble lithium bicarbonate, leaving most impurities as solids for removal via filtration.

Final conversion: The filtered lithium bicarbonate solution is heated to convert it back into high-purity, battery-grade lithium carbonate.

This is not recycling in itself, but a stage within the recycling process. The process consists of:

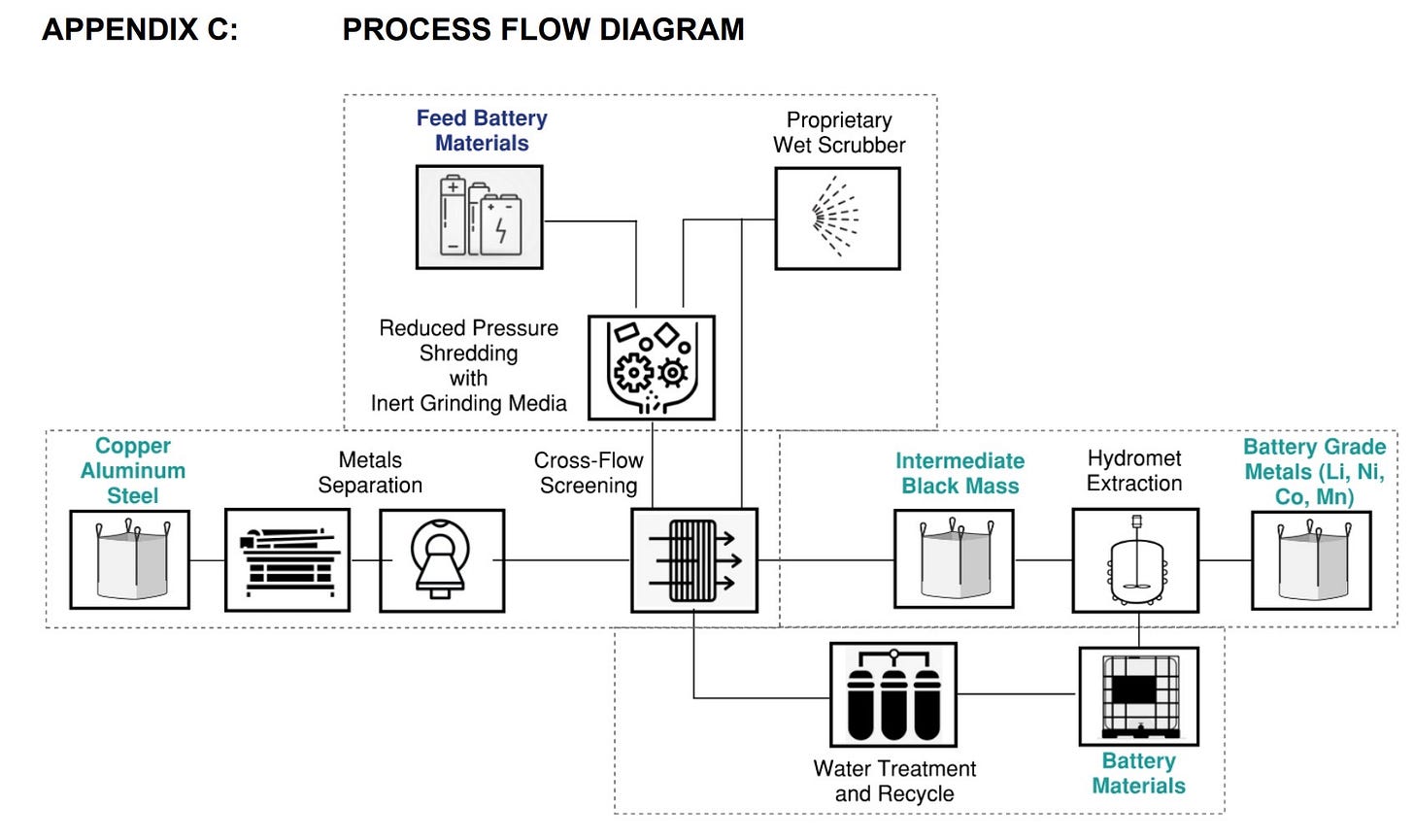

Collection

Black Mass Production

Black Mass Processing

The final stage, where this process fits, is sometimes called battery grade. However, not all platforms end there. Some stop at another intermediate, such as mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP). Others proceed past battery grade to engineered intermediates like precursor cathode active material (pCAM) or even cathode active material (CAM) itself.

The process in the article has nothing to do with the second stage of lithium-ion recycling, black mass creation, which makes the inclusion of this text somewhat irrelevant.

“No grinding agents”

That would be part of black mass production, where end-of-life cells and production scrap are shredded. It is also the stage where high temperatures are used, like in platforms that use pyrolysis (a thermal decomposition process performed at high temperatures in the absence of oxygen), which results in a black mass with the metals in a simpler form. This allows processes like direct carbonation to extract lithium with a much higher recovery rate.

The article specifically says that the process is performed at ambient temperatures, while CyLib will at one point heat the lithium solution (90-100C) during the stage where they create battery grade version. This step can be avoided if the initial black mass is purified beforehand or has been created using a black mass production process that generates very few impurities, like the one ABAT 0.00%↑ American Battery Technology Company developed and deployed at their Nevada facility, this is a process that uses the cell’s own failure mechanisms to, in essence, reverse the manufacturing process. Of course, in ABTC’s process they also utilize a form of early-stage recovery.

However, due to the proprietary nature, the exact process is unknown, but emissions filings suggest they use a form of hydrolysis to create an intermediate. This intermediate is then processed into lithium hydroxide monohydrate using a version of the process they created for their lithium extraction from claystone.

And to answer the question: Mith, could they use this on a battery and not black mass?

Just opening a cell and dropping it into water, then pumping in some CO2, will not work. On top of that a company would also have to ignore the safety hazards associated with this, mostly the risk of the water creating a short which will push the cell into thermal runaway. There is also the fact that LiPF6 (lithium hexafluorophosphate), when exposed to water, hydrolyzes to produce HF gas (hydrogen fluoride, a highly toxic and corrosive gas that can cause severe respiratory damage, chemical burns, and systemic toxicity).

Oddly enough, full thermal runaway tends to produce less HF overall compared to slower hydrolysis scenarios and due to the greater thermal stability of lithium iron phosphate, LFP cells are more prone to produce higher amounts of HF gas than NMC cells.

Direct carbonation only works on lithium once it has been dissolved into a solution. In unprocessed cells, the cathode metals are in a complex crystal lattice that is attached to an aluminum foil with binders, which prevent CO2 from reacting directly with the lithium. Without first converting the battery into a processed form like black mass, the lithium cannot be selectively precipitated as a carbonate.

But say they did this, I have read companies doing stranger things after all. The result would be extremely low recovery rates, the lithium that is in the electrolyte and locked away in other components of the cell would also be lost. As the mobile ion, lithium gets into everything, which is one of the reasons it has a lower recovery rate than the transition metals, you have to hunt it down and pry it out of everything. As such to access all of the lithium, cells require some form of pre-treatment to unlock it and make it easier to recover.

How about the other cathode metals? The article does mention them, even if the phrasing is odd, which may be because the text was originally in Chinese:

“The second part involves the use of cathodes that contain cobalt, nickel, and manganese. Following the process, instead of discarding them, the new method ‘upcycles’ these materials into useful catalysts.”

Direct carbonation cannot extract transition metals, and that is exactly why it is used. Lithium is extracted while the remaining metals stay in the solution as solids. After the early-stage recovery, many different processes can be used for those metals, from solvent extraction to ion exchange systems.

The use of “upcycling” in the article is also incorrect. In lithium-ion recycling, the primary goal is to recover materials from old batteries so they can be reused in new batteries, not to adjust or enhance them. The term has been misapplied, often by recyclers trying to make their process sound more innovative.

True upcycling means recovering CAM metals as a collective product and then adding additional metals to reach a target ratio for a new cathode. For example, recovered NMC622 can be adjusted into NMC811 pCAM for an OEM. Companies such as Ascend Elements (privately owned) and RecycLiCo (OTC: AMYZF TSXV:AMY FSE:ID4) focus on producing pCAM rather than individual salts, eliminating an additional step for OEMs. However, they will still need to produce or purchase the individual salts to adjust the ratio.

Ascend Elements also uses carbonation, but through an indirect route. The graphite already present in the anode fraction of the black mass supplies the carbon. By using this graphite as a reagent, the process produces battery grade lithium carbonate in situ while leaving the remaining metals ready for upcycling into new cathode material.

Also, this part is rather well…

“instead of discarding them”

Right now the majority of feedstock for lithium-ion recyclers are high-nickel cells like nickel cobalt manganese (NMC), which are mostly used in EVs and also in power tools. The second is lithium cobalt oxide (LCO), which is the dominant chemistry for digital devices like cell phones, tablets, and laptops. But LFP has now secured around 45% of the EV market, and many power tool OEMs are transitioning to LFP as well.

While LFP has many advantages due to its cost and thermal stability, it is less profitable to recycle. This is because the only real value metal in LFP is lithium. With NMC there is the nickel and cobalt, which makes it profitable without a high lithium price or subsidies.

There is also another problem when it comes to LFP and carbonation. When processed, LFP produces lithium phosphate, which is not highly water soluble. This solid lithium phosphate acts like a chemical glue that locks the lithium into the solid black mass. Because it does not dissolve, you cannot simply wash or filter the lithium away from the iron and graphite.

In direct carbonation, this creates a major bottleneck. Lithium has a much higher affinity for phosphate than for carbonate, meaning it precipitates as an insoluble solid faster than lithium carbonate. Instead of a clean recovery, the lithium remains locked inside the black mass.

There are workarounds, such as what Cylib is doing with a solvent called Cyanex 936P. This is a lithium-selective solvent that, when introduced during the carbonation process, extracts the lithium ions before they can bond with the phosphate. By pulling the lithium into a liquid organic phase, Cylib effectively lifts it away from the solid iron and graphite. Once the phosphate solids are filtered out, the lithium is released from the solvent to react with CO2, allowing the production of high-purity lithium carbonate.

But back to the cathode metals, no one is or was tossing metals like nickel and cobalt away. In fact, until a few years ago lithium was often discarded because the value of recovering it was simply not there. This, of course, changed with EVs.

Seems every week, a “new” process is hyped as the next evolution, in lithium-ion recycling. Most of these stories follow the same familiar script, designed to capture attention rather than reflect reality.

More efficient.

Better for the environment.

Able to process material that was previously discarded.

What these articles often present as evidence are vague or incomplete descriptions of older processes. In reality, today’s lithium-ion recycling platforms already employ some of the most advanced waste collection, recovery, and containment systems in the world. When a company launches a recycling platform, it is rarely static. The next generation is already under development, with the one after that sketched out on a whiteboard.

While there have been real innovations over the past few years, translating lab scale concepts, where most of the processes the media cover still reside, into commercially viable operations is far more complex than these articles suggest.

Overall most if not all of the processes highlighted in the media, including on sites like Interesting Engineering, are simply rebranded versions of systems already in use, as is the case with this fizzy method.

If you found this article valuable, consider becoming a subscriber. The Critical Materials Bulletin is supported by readers, and for $5 a month or $55 a year you can help fund research that produces clear, no nonsense reporting that informs and advances the discussion on critical materials and battery metals.

DISCLAIMER: This article should not be construed as an offering of investment advice, nor should any statements (by the author or by other persons and/or entities that the author has included) in this article be taken as investment advice or recommendations of any investment strategy. The information in this article is for educational purposes only. The author did not receive compensation from any of the companies mentioned to be included in the article.